As you may know, my wife Stephanie Lisciandro, DVM, DACVIM (SAIM), was trained at The Animal Medical Center in the mid 1990s. There she was taught to look at the caudal vena cava (CVC) and hepatic veins for right-sided volume overload and right-sided congestive heart failure by Dr. Richard “Scotty” Scott, DACVIM (SAIM).

In 2005, I created AFAST® and TFAST® while as part of my clinical research requirement during my ECC residency training while Stephanie was working as an internist at a referral practice, and then doing mobile ultrasound and consulting in San Antonio, Texas. At that time, she had little interest in AFAST® and TFAST® until 2010, when she had enough local referring practices begin asking her about what her “husband, Greg (me)”, was doing with this AFAST® and TFAST® ultrasound at The Emergency Pet Center in San Antonio.

So, she asked me…and I explained to Stephanie what we were doing at The Emergency Pet Center, the speciality referral ER and ICU practice at which I was working. I explained to Stephanie how we were performing the AFAST® and TFAST®, our AFAST® and TFAST® objectives, and how we recorded our AFAST® and TFAST® findings on Goal-directed Templates.

Stephanie was intrigued and then suggested that we add imaging and characterizing the CVC and hepatic veins at the AFAST® and TFAST® Diaphragmatic-Hepatic (DH) View. She taught me the general CVC and hepatic vein principles and we immediately began imaging the CVC and its associated hepatic veins. It was easy. No additional AFAST® and TFAST® probe manuevers were necessary, as the CVC was right there at the DH View, just as Stephanie had told me. What a great way to assess volume status over central venous pressure (CVPs) that an invasive central line, then using a manometer. Moreover, in 2013, 3 years after we began CVC and hepatic venous assessment, a landmark review was published on the human side, that stated that the use of central venous pressure measurements was unreliable for guiding fluid therapy, and that the intervention should be abandoned.

Our use and teaching of CVC and hepatic venous characterization was far in advance (4-5 years) of any other veterinary point-of-care colleagues considering such a notion. At the time I was teaching AFAST® and TFAST® and presenting this new concept at the SOUND Academy (2010-2016) and at veterinary conferences nationally and internationally. I also included this concept in our 1st edition of our textbook Focused Ultrasound for the Small Animal Practitioner for the Small Animal Practitioner, Wiley ©2014.

In fact (circa 2014), we helped train and educate my Canadian and European colleagues on how to image and characterize the CVC (see the figure at the end of this Blog, they still use my images, without proper citation). So, I give all the CVC volume status credit to my wife Stephanie (and Dr. Richard “Scotty” Scott), on making this paradigm change in veterinary medicine. Now in hindsight, I recall during patient rounds as an intern at The Animal Medical center, “The AMC”, the notations of the CVC and hepatic veins on our ultrasound reports by “Scotty” back in 1991-1992, i.e., “the patient has a distended caudal vena cava and hepatic veins, discontinue fluids, consider an echocardiogram.”

We hope you enjoy this ECC and IM Blog and it will make a difference in patient management.

Some Clinical Pearls for Imaging the Caudal Vena Cava

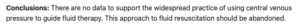

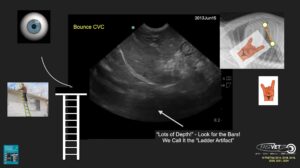

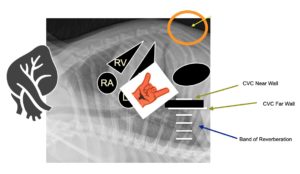

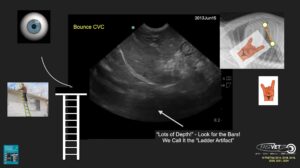

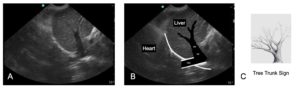

The figure shows the classic AFAST® and TFAST® DH View and the location of the CVC, along with the narrow column of reverberation-mirror artifact (called the “ladder artifact”), extending from the CVC’s far wall through the far field. I liken this to a ladder being placed against the roof and climbing up the “ladder artifact” to the eaves of the roof top, the longer white line representing the far wall of the CVC. Then above the far wall, there is the black blood filled tube, and then the break or short bar at the break of the diaphragm for the near wall.

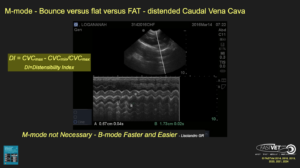

Freeze and scroll through frames looking for the largest gape in the CVC. That would be your “CVC maximum height measurement”, although we use the “eyeball method” of “FAT” (distended with little change [<10%] in maximum height over cardiac and respiratory cycles, “volume intolerant”), “flat” (small with little change [<10%] in maximum height over cardiac and respiratory cycles, “volume starved” or hypovolemic) and a “bounce” (a CVC height change of ~35-50% in its height over cardiac and respiratory cycles). So several seconds is captured and scroll through frames to assess since trying to correlate cardiac and respiratory cycles is more of a theoretical proposition.

Holding the Probe

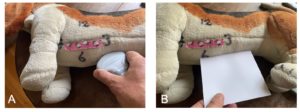

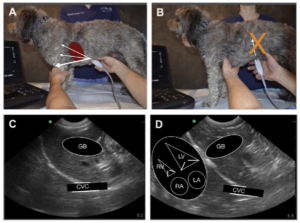

The key is holding the probe so that your scanning plane is fanned through the caudal vena cava (CVC) in “true fashion” along its longitudinal course anatomically. Holding the probe with your “hand on top” rather than like a pencil keeps the scanning plane “true.”

Best for SUCCESS – you must be longitudinal as shown here!

Note that the hand is on “top of the probe” – SUCCESS – with the thumb on the marker and the index finger on the other end as shown in A). By doing so, the scanning plane is like the piece of paper in B) and in a longitudinal plane. By holding the probe in this manner, you can fan in a “true” longitudinal plane. Staying “true” to the longitudinal plane will give you a good image of the CVC and its associated hepatic veins. Note a macro convex probe rather than the smaller micro convex probe is used for illustrative purposes.

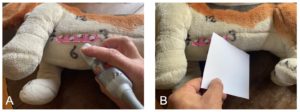

This is a FAIL – holding “like a pencil” obliques the CVC and won’t be accurate!

Note that the probe is held “like a pencil” – FAIL – as shown in A). By doing so, the scanning plane is like the piece of paper in B) and obliqued which will not provide a good image of the CVC and one accurate for measuring.

A Final Comparative Probe Holding Image!

Note the difference in how the probe is held in the “Good! – SUCCESS” and “Bad! – FAIL” images.

Additional Pearls for Imaging the CVC are 1)Increase your depth as much as possible (the FASTVet DH “15 cm Rule”) because you will then quickly see the CVC “ladder artifact” in smaller and medium sized patients, 2) The CVC is “a Texas Longhorn away” from the “cardiac bump”, meaning that where the heart is opposed to the diaphragm called the “cardiac bump”, the actual CVC is a distance away and by using the “Texas Longhorn Sign” as shown below, it gives you an idea of where to look on the screen for the CVC as it traverses the diaphragm (a FASTVet Trick of the Trade that works in all quadrapeds), and 3) Rocking cranially to “move the stomach caudally off the screen”, because of its common gas shadowing. Also of note the CVC is slightly toward the tabletop when a patient is in right lateral because it runs longitudinally or along the long axis of the patient as it courses from the right atrium and through the diaphragm.

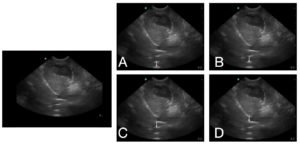

Quiz – Can You Properly Identify the CVC?

Note the image to the left without any arrows is the patient’s DH view. In A) – D) and arrow is placed with possible locations of the CVC. Which of these views correctly identifies the CVC. The answer at the bottom of this Blog.

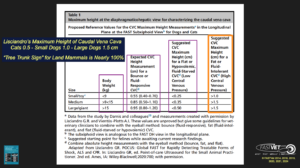

Measuring the CVC Height

Measuring the “maximum height” (it’s not a diameter, there is no circle) and using our FASTVet CVC Maximum Height Chart to categorize as “fluid responsive” (“bounce”), “fluid starved” (flat), or “fluid intolerant” (FAT). The best manner to find the CVC maximum height is to image the CVC over several seconds because it has respirophasic variation, then freeze and roll the track ball through frames finding its maximum height. Although, keep in mind that the “eyeball characterization”, i.e., “bounce”, “FAT”, or “flat” of the CVC trumps the maximum height.

The “FASTVet CVC Maximum Height Rule” is easy to remember – “cats maximum CVC height should be < 0.5 cm; small dogs < 9 kg maximum CVC height should be < 1 cm; and larger dogs > 9 kg the maximum CVC height should be < 1.5 cm”

*So Remember Greg’s Rule for “Maximum CVC Heights” as “< 0.5 cats to < 1.0 small dogs to < 1.5 large dogs”

Hepatic Venous Distension and the “Tree Trunk Sign” – Another FASTVet Original Term

We have shown and published (Chou et al. 2021) the “Tree Trunk Sign” (our term published in the 1st edition of our textbook and now in our peer-reviewed literature) as, depending on how you read our findings, 96% specific and 84% sensitive for the presence of right-sided congestive heart failure (R-CHF). In normalcy you do not expect to see hepatic venous branching. This Chou et al. study is available open access and has some interesting, easily readable tables with measurements of the caudal vena cava and presence of gallbladder wall edema.

FASTVet Premium Members – Watch the “Power of the DH View Webinar” for more information.

Click here for the LINK to the “Power of the DH View” Webinar from March 2022. Please send any comments to Dr. Greg Lisciandro, DVM, DABVP, DACVECC to LearnGlobalFAST@gmail.com

Final Comments

1) B-mode or M-mode for measuring the CVC maximum height? You may use B-mode or M-mode, however, B-mode is usually much easier (unless you are a cardiologist or use M-mode a lot).

2) There are several clinical studies on assessing the CVC, as itself and comparing to the size of the aorta, at various locations. It makes the most sense that the most sensitive location is at the AFAST – TFAST DH View, being as close to the right atrium as possible.

3) Distensibility Index is purely academic. Use the “eyeball method” of “bounce”, “FAT”, or “flat. As an FYI – CVC Distensibility Index (DI) is calculated as the Difference of CVC Maximum to CVC Minimum Height ÷ CVC Maximum Height

4) Myth? – Excessive pressure collapses the CVC at the DH View? My colleagues like to say this, however, I have never seen this. They must be pushing really hard at the DH View. The slide that they used with my video for Pitfalls is not properly cited, they act as if it were their video, and it is inaccurate as it does not represent pressure artifact. This is my image they are using improperly and without proper citation and acknowledgment. This slide of mine was shown by Dr Gommeren was used at the ACVECC PGR Course 2024.

Quiz – Answer is D.

gl/GL 2-27-2023

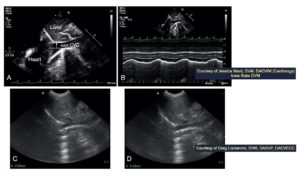

Addendum

An example of the probe placement and rocking cranially in a standing patient. The image of from the 2nd edition of our textbook, a great resource for you, that may be purchased through Amazon. Note in A) the probe marker is directed far cranially bringing the white curved line along the diaphragm close to the probe head, close to the near field, as shown in C) and D). In contrast in B), the probe is directed toward the spine, which will generally be a fail for imaging the CVC, because it will bring the stomach and its shadowing through the CVC area of interest. In D) the overlay shows you the orientation of the heart chambers relative to the diaphragm. Note the left heart is along the diaphragm and this holds true for all quadrapeds. In contrast, people (bipeds) have the right heart closest to the diaphragm.