What is AFAST®?

FAST is an acronym that stands for Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma. It is an ultrasound exam developed by trauma surgeons in the 1990s and used as a screening test for the detection of free fluid in the abdominal cavity, ascites, and the pleural cavity including pleural effusion and pericardial effusion. In 2004 the translational study from humans to dogs was published by Boysen and colleagues out of Tufts.

The next year we developed AFAST® as part of my clinical research requirement for my emergency and critical care residency training out of the Emergency Pet Center, San Antonio, Texas. We made changes from the original format by renaming its views and adding the umbilical view. These views were named according to their target organs to improve teaching (the sonographer knows what fundamental anatomy to expect) while making AFAST® a screening test for not only free fluid but also soft tissue abnormalities (a radical change).

Moreover, scanning planes, screen orientation, and probe manipulations were standardized to enhance the learning process. Patients were no longer shaved (a radical change). Right lateral was preferred over left lateral recumbency because in right lateral fundamental echocardiography, electrocardiography, imaging the gallbladder and caudal vena cava, and performing abdominocentesis were more amenable. However, AFAST® could also be performed in standing position being even lower impact for the patient (a radical change).

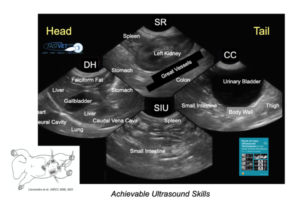

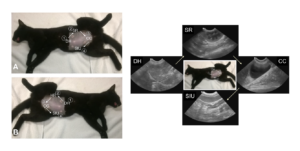

Figure. The first 4-views of AFAST® are used for abdominal fluid scoring. The Hepato-Renal view has been renamed the Spleno-Intestino Umbilical (SIU) view. Note not shown is the Hepato-Renal 5th Bonus view. The ultrasound images are examples of the starting point and the depth/relative proportionality used at each respective view regardless of mammalian species. This material is reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Point-of-Care Ultrasound Techniques for the Small Animal Practitioner, 2nd Edition, Wiley ©2021 and Greg Lisciandro, Hill Country Veterinary Specialists, FASTVet.com.

Figure. It is easy to master the fundamental AFAST® anatomy at each respective AFAST® view in longitudinal orientation making everything spatially like a lateral abdominal radiograph. This material is reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Point-of-Care Ultrasound Techniques for the Small Animal Practitioner, 2ndEdition, Wiley ©2021 and Greg Lisciandro, Hill Country Veterinary Specialists, FASTVet.com.

When Should You Perform AFAST®?

The mindset was to use AFAST® as “an extension of the physical exam.” In other words, everyday ultrasound for nearly every patient. An AFAST® is a <3-minute test with minimal ultrasound training.

Indications for an AFAST®

Initially we used AFAST® for trauma, triage, and tracking (monitoring). To avoid the onslaught of confusing acronyms in human medicine with formats having similar objectives, we added the T3 (trauma, triage, tracking) to our acronyms, i.e., AFAST3. However, we quickly morphed to the following clinical applications:

- Any abnormal or questionable patient

- Your new preanesthetic screening test

- Perioperative monitoring

- Semiannual and annual visits

- Geriatric screening test

- During patient rounds and recheck exams

AFAST® has become so widespread for these indications that we have more recently dropped the T3. The AFAST®approach allows for cost-effective imaging that otherwise would not be performed. For example, we out-price ourselves with radiography and complete abdominal ultrasound studies. Thus, many patients get sent home without any imaging. AFAST® gives you a “baby step” to screen for the need for additional imaging including radiology, complete ultrasound studies, and computed tomography (CT).

By “seeing” your problem list (evidence-based information) the diagnostic plan is better streamlined and treatment more accurately determined. And, if you think about it, an AFAST® is a better imaging test than abdominal radiography for 95% of our patients.

Advantages of AFAST® and Its Abdominal Fluid Scoring System

AFAST® is rapid, radiation sparing, low impact (minimal restraint), and real-time information (no delay) right there at your patient’s side. With proper training and minimal experience an AFAST® exam should take < 3-minutes.

AFAST® can semi-quantitate the volume of ascites (free fluid) by the AFAST®-applied abdominal fluid scoring system providing more information than a “flash” or POCUS abdomen that stops at a binary assessment of positive or negative ascites (free fluid). This is especially helpful for anticipating degree of anemia in bleeding patients and volume loss in non-hemorrhagic effusions.

This is a simple 0-4 system (0, negative; 1, positive) scoring the first 4 AFAST® views – the Diaphragmatico-Hepatic (DH) View, the Spleno-Renal (SR) View, the Cysto-Colic (CC) View, and the Spleno-Intestino Umbilical (SIU) View, previously named the Hepato-Renal Umbilical (HRU) View. The Hepato-Renal View is called the Hepato-Renal 5th Bonus View because it is scored but not part of the total abdominal fluid score (see Goal-directed Template for recording findings). This system provides an objective number (AFS, abdominal fluid score) and records where the patient is positive and negative, which may have clinical relevance as to the origin of the problem over subjective assessments for fluid, i.e., trivial, mild, moderate, and severe.

Modification of AFAST® and Its Abdominal Fluid Scoring System

Based on more recent clinical research we have modified the abdominal fluid scoring system by assessing scores of 0, 1/2, and 1 at each AFAST® view. The “1/2” is considered a “weak positive” and the “1” a “strong positive” and can be agreed upon as a practice by the visual method or the measurement assessment using maximum dimension of over or under 5 mm for cats and over and under 1 cm for dogs. This new system better categorizes cases (see Figure).

Small versus Large Volume Bleeder/Effusion

Originally, we differentiated small volume bleeder from large volume bleeder by the abdominal fluid score (AFS) being “AFS 1 and 2” for “small volume” and “AFS 3 and 4” for “large volume.” With the modification of the abdominal fluid scoring system, we now have small volume as AFS < 3 and large volume as ≥ 3.

In bleeding patients, we do not expect small volume bleeders to become anemic directly from their intra-abdominal bleed (or hypovolemic) because there is not enough volume as a general rule. Thus, if a small volume bleeder is anemic then it cannot be directly from the intra-abdominal hemorrhage and is one of 4 major rule outs: 1) bleeding somewhere else so do a good physical exam and a Global FAST® (to check for other internal sites of bleeding), 2) the patient has pre-existing anemia, 3) hemodilution from fluid resuscitation, and 4) lab error (spin down a PCV/TS and run an automated HCT).

As for non-hemorrhagic effusions, hypovolemia is not expected in small volume non-hemorrhagic effusions versus being expected in large volume non-hemorrhagic effusions. Using this system, patients may be tracked for static, worsening (increasing score), and resolving (decreasing scores) forms of ascites.

Figure. The first 4-views of AFAST®, the DH, SR, CC, and SIU, are used for abdominal fluid scoring. Each respective view is scored as positive or negative. Positive views have been more recently designated as “weak positives” scored “1/2”, and “strong positives” scored “1.” The maximum score remains the same as “4”; however, using the new model helps better differentiate small volume (< 3) versus large volume (≥ 3) effusions. Using this system allows for tracking patients. This material is reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Point-of-Care Ultrasound Techniques for the Small Animal Practitioner, 2nd Edition, Wiley ©2021 and Greg Lisciandro, Hill Country Veterinary Specialists, FASTVet.com.

The Bleeding Patient and Its Subsets

Blunt Trauma. AFS of 3 and 4 dogs often require blood transfusions, but not always. These patients are typically managed medically with titrated intravenous fluid therapy, blood products and uncommonly require surgical intervention. In dogs the percentage of hemoabdomen to uroabdomen has been reported to be 98% hemoabdomen and 2-3% uroabdomen. Ruptured gallbladder, although uncommon, is another rule out. Cats do not survive large volume bleeds. A surviving cat with a large volume effusion associated with blunt trauma is more likely to have a uroabdomen. Any positive is considered major injury until proven otherwise and should be followed with serial AFAST® (better serial Global FAST®).

Penetrating Trauma. Any positive is considered a surgical candidate because it is difficult to assess internal injury without the gold standard test of computed tomography (CT). In cases not taken to surgery, serial AFAST® (better Global FAST®) are performed until the attending is absolutely certain there is no surgical problem(s), i.e., septic abdomen, pyothorax, etc. AFAST® should be repeated every 4-8 hours in hospital and on patient rounds and outpatient recheck exams if the patient is not clinically normal.

Surgical Trauma. “If it’s an AFS 3 or 4 you should explore” in the absence of coagulopathy is our mantra. Every heartbeat is depositing more and more blood into the abdominal cavity even in those stable large volume bleeders.

Non-trauma. Using the AFS and comparing to the venous packed cell volume (PCV), the attending can determine acute versus chronic bleed. For example, an AFS of 1 or 2 should not have a PCV of 18% unless there is chronic anemia (due to such things as intermittent bleeds from a tumor, bone marrow disease, bleeding somewhere else). In the absence of a coagulopathy and anaphylaxis, clinical judgment is used to assess if and when surgical intervention takes place. Global FAST® is a rapid way in which to screen for obvious metastasis and stage the patient as localized versus disseminated disease. Keep in mind not all disseminated disease is disseminated cancer, i.e., fungal and verminous disease.

Clinical Pearl. Always spin down and test the abdominocentesis sample. Judging it grossly is prone to mistakes and a PCV as low as 3-5% can appear grossly bloody when the fluid is in fact blood contamination. A hemoabdomen is considered by some as a PCV > 10%; however, the author considers a hemoabdomen to be an abdominal PCV of ≥ 50% of the venous sample.

Clinical Pearl. The FASTVetTM Bleeding Rule. When bleeding stops and coagulopathy when present is corrected, expect the AFS to decrease markedly and be close to 0 if not negative within 48-hours. If your patient is not following this rule, then further investigation is required to determine the source of bleeding.

Hemoabdomen in Cats

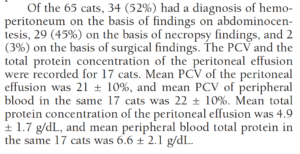

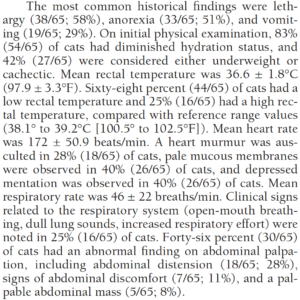

There are sparse studies of hemoabdomen (hemoperitoneum) in cats. In a study by Mandell et al. published in JVECC 1995 entitled “Hemoperitoneum in 16 Cats: 1986-1993”, 12 of the 16 had the liver as the source of their bleeding. In a more recent case series entitled “Spontaneous Hemoperitoneum in 65 cats: 1994-2006” published by Culp et al. in JAVMA 2010, they found the following relevant results: 1) 46% of cats had neoplasia most commonly hemangiosarcoma; and 54% were non-neoplastic with an array of abnormalities, 2) physical exam findings were non-specific with only 8% of cats having a palpable abdominal mass and 28% with abdominal distension, 3) abdominocentesis was performed in 34/65 (52%) of which only 17/65 (26%) or 17/34 (50%) cats had their hemorrhagic fluid spun down as a packed cell volume. When abdominal effusion PCV was compared to venous PCV in the 17 cats they nearly matched as expected for a hemoperitoneum diagnosis at 21% and 22%, respectively.

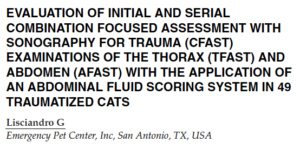

In Lisciandro’s 2012 JVECC Abstract entitled “Evaluation of Initial and Serial Combination FAST (CFAST) Examinations of the Thorax (TFAST®) and Abdomen (AFAST®) with the Application of the Abdominal Fluid Scoring System in 49 Traumatized Cats”, there were too few cats (14%, N=7) that were AFAST®-positive with only 1 of which was a confirmed hemoabdomen. Thus, there were no numbers to correlate abdominal fluid score (AFS) with degree of anemia. The the conclusion was drawn by Lisciandro that “cats don’t survive large volume intra-abdominal trauma-related bleeds” and that “surviving cats often have other types of free fluid, i.e., uroabdomen.”

Clinical Cat Pearls:

- Use AFAST® and Global FAST® as an extension of the physical exam in all cats especially those that are abnormal whether trauma or non-trauma because physical exam findings are insensitive and unreliable.

- The most common cause of spontaneous hemoperitoneum in cats appears to be the liver in both neoplastic and non-neoplastic subgroups.

- The teaching paradigm needs to be changed in that ALL cats having abdominocentesis should always have the PCV of the abdominal effusion compared to the venous PCV because a PCV as low as 3-5% can appear grossly hemorrhagic and be misinterpreted with potential catastrophic consequences for the patient.

- In traumatized cats, the most common cause of free fluid is variable and uncommonly hemorrhagic (hemoabdomen < 10%) in direct contrast to dogs (blunt trauma dogs hemoabdomen in 97-98% of cases).

AFAST®: Talking Points for Clients

The spiel is important to be standardized within the practice so that your clients aren’t confused. An example of a spiel would be as follows:

“We are going to perform in AFAST® ultrasound exam on your pet. AFAST® is a screening test looking for any free fluid, forms of peritonitis, within the abdominal cavity of your pet. Free fluid could be blood, pus, or something else. We also are looking for any obvious soft tissue abnormalities in your pet’s major abdominal organs.”

Optional – “If you presented at Methodist Hospital here in San Antonio, a FAST exam would be similarly used as a first line screening test providing information point-of-care without delay that better helps lead to a diagnosis and more accurate treatment in many instances.”

For critical triaged patients – “If there is free fluid that is safely accessible, may I use a needle about the same size we vaccinate with to sample the fluid and test it.”

This quickly gives you permission to do the AFAST® and abdominocentesis when minutes count rather than going back and forth to the client for permissions.

AFAST®: Recording Findings

Goal-directed templates (GDTs) for recording your findings are a must for success. GDTs keep you disciplined and on task. AFAST® is performed the same order every time just like a cardiologist a radiologist perform their examinations the same way every time. GDTs also give you value for comparison to future exams for you and for your colleagues.

Examples of GDTs may be found at our website FASTVet.com on our Free Resources page.

References and Further Reading

- Lisciandro GR, Lagutchik MS, Mann KA, et al. Evaluation of an abdominal fluid scoring system determined using abdominal focused assessment with sonography for trauma (AFAST) in 101 dogs with motor vehicle trauma. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2009; 19(5):426-437.

- Lisciandro GR. Focused abdominal (AFAST) and thoracic (TFAST) focused assessment with sonography for trauma, triage and monitoring in small animals. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2011;20(2):104-122.

- Lisciandro GR. Lisciandro GR. The use of the diaphragmatico-hepatic (DH) view of the abdominal and thoracic focused ultrasound techniques with sonography for triage (AFAST/TFAST) examinations for the detection of pericardial effusion in 24 dogs (2011-2012). J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2016;26(1):125-31.

- Lisciandro GR, Fosgate GT, Romero LA, et al. The expected frequency and amount of free abdominal fluid estimated using the abdominal FAST-applied abdominal fluid scores in healthy adult and juvenile dogs. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2021 31(1):43-51.

- Lisciandro GR. Chapter 6: POCUS: AFAST-Introduction and Image Acquisition. In Point-of-care Ultrasound Techniques for the Small Animal Practitioner, 2nd Edition, Ed. Lisciandro GR. Wiley Blackwell: Ames IA 2021.

- Lisciandro GR. Chapter 7: POCUS: AFAST-Clinical Integration, Point-of-care Ultrasound Techniques for the Small Animal Practitioner, 2nd Edition, Wiley-Blackwell: St. Louis, ©2021.

- Lisciandro GR. Cageside Ultrasonography in the Emergency Room and Intensive Care Unit. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2020;50(6):1445-1467.

- Lisciandro GR. Chapter 3: Point-of-Care Ultrasound. In Small Animal Diagnostic Ultrasound, 4th Edition, Eds. Mattoon JS, Sellon R, Berry CR. Elsevier: St. Louis MO, 2021.

- Chou Y, Ward JL, Baron LZ, Murphy SD, Topf MA, Lisciandro GR, et al. Focused ultrasound of the caudal vena cava in dogs with cavitary effusions or congestive heart failure: a prospective observational study. PLoS One 2021;16(5):e0252544. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0252544

- Lisciandro GR, Gambino JM, Lisciandro SC. Case series of 13 dogs and 1 cat with ultrasonographically-detected gallbladder wall edema associated with cardiac disease. J Vet Intern Med 2021 35(3):1342-1346.

gl/GL 4-9-2024